Solar Eclipse Geometry

Estimated reading time: .

Far too much information about why the moon’s shadow does what it does in an eclipse.

ContentsIntroduction

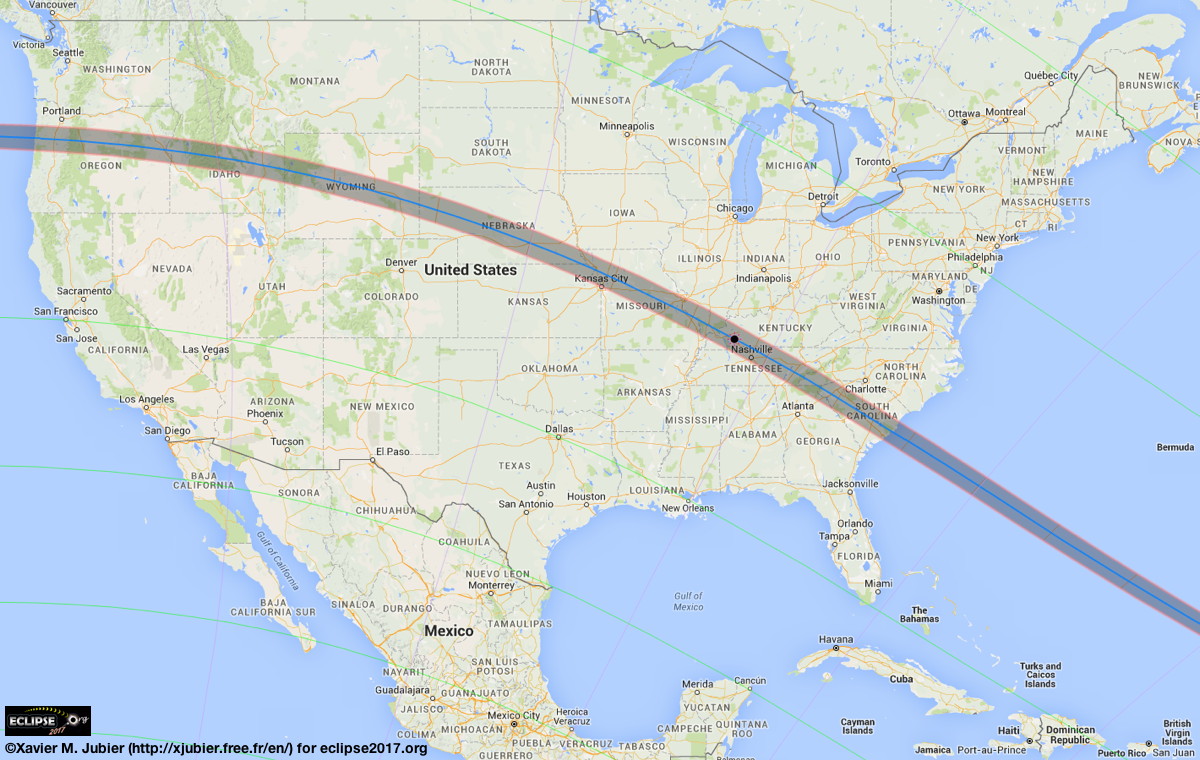

Later this month, a full solar eclipse will occur that transits the entire width of the United States of America, running from Oregon to South Carolina.

A map of the eclipse track over North America. Originally from Eclipse 2017. {:tag=”cite”} {:tag=”figcaption”}

I’ll be in Driggs, ID to watch it, which is fairly close to the path of full totality, but it won’t be perfect. Still extremely cool, though.

As with all things space-related, there are a lot of innocent misconceptions about this and a few downright malicious items of misinformation going around, and as I have an undergrad math/physics education and work for a satellite company, I’ve opted to provide an explanation about some of these, to spread the light of knowledge in these moon-darkened times.

The main question I’ve seen is “why does the eclipse shadow transit from west to east when the moon transits the sky from east to west?” and that’s a very good question. Don’t mock people for asking it; it’s a legitimately good question and is rooted in ten thousand years of human tradition of not grokking the mechanics of the solar system from mere Earth-surface observation.

So let’s answer it!

Glossary

I’m going to use some jargon, and explicitly not use some common terms. It’s important that vocabulary is mutual, so any terms that are uncommon will be defined here.

- Sol: The sun

- Terra: The planet Earth

- Luna: Earth’s only moon. I’m going to use these names from here on.

- North: The direction parallel to Earth’s axis of rotation, towards the star Polaris

- South: The direction parallel to Earth’s axis of rotation, away from the star Polaris

- East: The direction going forward with Earth’s spin, that is, prograde with the surface of the planet

- West: The direction going backward against Earth’s spin, that is, retrograde with the surface of the planet

- tangential velocity: The linear velocity of the surface of a rotating object. It is perpendicular to the object’s radius, pointing in the direction of rotation/revolution.

- arc velocity: Velocity across a backdrop, measured in terms of angle traveled. This is the measure used for travel of objects across the sky, for example.

- prograde: In the direction of travel, either of revolution or of rotation. In our solar system, this is typically counterclockwise when viewed from the North.

- retrograde: Against the direction of travel, also applicable to revolution or rotation

- barycenter: The mutual point about which two bodies orbit. For example, the Earth and Moon mutually orbit a barycenter that is within the Earth’s crust, which is part of the reason the moon changes apparent size.

- revolution: The elliptical path traveled by an orbiting body around a barycenter, or the act of following this path, or one complete circuit of this path. Think race courses.

- rotation: The act of rotating about an axis inside an object, or one complete circuit of this behavior. Think tops, or to make this more relevant to 2017, fidget spinners.

- orbital inclination: The degree of tilt of an orbital plane from some reference plane.

- ecliptic: Terra’s orbital plane, which we use as the reference measurement for most other bodies orbiting Sol.

- \(\tau\): The correct circle constant, equal to \(\frac{C}{r}\) or \(2\times\pi\). Its numeric value is \(6.28318…\)

- radian: The section of a circle’s circumference with arc length equal to that circle’s radius. There are \(\tau\) radians in a circle.

I will be using “East” and “West” solely to refer to directions on the surface of the earth, and will use “prograde” and “retrograde” to refer to directions in orbit.

I will also use “inward” to be the direction towards the barycenter of an orbit, and “outward” to be away from the barycenter.

I will not use the words up or down at all.

Setting the Scene

The solar system is not neatly aligned. Terra rotates around an axis that is not the axis about which it revolves. Furthermore, Luna revolves around Terra on an orbit that is also inclined relative to Terra’s orbit.

The fact that Luna’s orbit is tilted, and has further complexities, is why solar eclipses are so rare. Luna needs to cross the ecliptic (heading either North or South) while directly between Terra and Sol, so that its shadow falls on Terra‘s surface.

So, the Sol-Terra-Luna system will look like this, both when viewed from far Northward or Southward, and when viewed from in the ecliptic, far prograde or retrograde.

.-.

/ \

( Sol ) L (T)

\ / ^ Luna ^ Terra

`-'Rise in the East, Set in the West

Let’s briefly talk about the sun and moon both rising in the east and setting in the west. These are both due to the fact that the Earth is rotating about its axis.

For Sol, as Terra rotates, a point on its surface is moving counterclockwise (when viewed from far North).

E S (T)- <--observer WMidnight E|W S (T)Dawn W S -(T) ENoon S (T) W|EDusk

As these terrible ASCII diagrams show, as a fixed observer on Terra’s surface rotates, Eastward will cross from nightside to dayside first (Sol rising in the East), then the observer will move retrograde during the day so that Sol appears to move towards West, and then West will be the last to cross from dayside to nightside (Sol setting in the West).

The moon follows this same appearance, and I’ll do the math for why that is now.

Arc Velocity in Terran Sky

The motions of Sol and Luna in Terra’s sky, from the perspective of a fixed observer on Terra’s surface, are governed strongly by Terra’s rotation, and are best discussed in arc velocity: fractions of a circle per unit time. I’ll be using radian for my units, not degrees.

I’m going to solve this from first principles; skip ahead if you aren’t my professor and don’t want to check my work.

We start with the period of rotation of the Earth.

Note that this period of rotation is the sidereal day: the period required for Terra to have completed one rotation relative to the far stars, not to the sun. After one sidereal day, an observer who began under solar noon would be earlier in the solar day, with the sun slightly to the east of where it had previously appeared to be. Astronomy is complex. {:tag=”aside” .block-info .iso7010 .m001}

- Rotation Period of Terra: \(p_{T} := 86164.1 s\)

It takes one sidereal day to travel \(\tau\) radian, so the arc velocity is just \(\frac{\tau}{86164.1 s}\), which comes out to:

- Arc Velocity of Terra: \(\omega_{T} := 7.29212 \times 10^{-5} \frac{rad} {s}\)

Arc Velocity of Sol, from Terra

The motion of Sol across the sky is the difference of this arc velocity minus the arc velocity of Terra in its orbit around Sol, which is roughly \(\frac{1}{365.26}th\) of Terran rotational arc velocity.

So in short, the arc velocity of Sol in Terran sky is roughly 73 microrad/s, which not coincidentally is \(\frac{\tau}{2}\) radian per 12 hours.

Arc Velocity of Luna, from Terra

Like Sol, Luna’s arc velocity is the difference of Luna’s orbital arc velocity and Terra’s rotational arc velocity. However, the orbital arc velocity is not as trivial as it was for Sol, so I am going to calculate it.

Our starting data, or axioms, are:

- Orbital period of Luna: \(p_{L} := 2.3606 Ms\) (Megasecond, \(10^{6}\))

- Arc velocity of Terra, calculated previously.

Following the same formula for arc velocity, we have:

- [Arc velocity of Luna][5]: \(\omega_{L} = \frac{\tau}{p_{L}} = 2.6617 \times 10^{-6} \frac{rad}{s}\)

Both arc velocities are in the same direction, as almost all angular velocities in the solar system are prograde.

If Terra did not rotate, Luna would advance prograde (West to East from the surface perspective) at a rate of 2 microrad per second. However, Terra does rotate, thirty times faster than Luna advances. This means that the Terran surface significantly outpaces Luna in terms of apparent position in the sky and so Luna moves from East to West.

Arc Velocity Conclusion

Sol moves across the sky, East to West, at 73 microrad/s. Luna moves across the sky, East to West, at 2 microrad/s.

When we watch the eclipse, the moon doesn’t overtake the sun; the sun races behind the moon.

It will appear that the moon is overpassing the sun, because we as casual observers do not have a fixed frame of reference to show both of them moving Westward in the sky for a few minutes and our brains are trained to perceive this event (far object briefly occluded by a near object) as the near object moving faster.

Next up: the shadow.

Tangential Velocity in Orbital Plane

We care about two components here: the tangential velocity of Luna in its orbit, and the tangential velocity of the Terran surface in its rotation.

During eclipse, Luna is inward towards Sol of Terra, and is moving retrograde relative to Terran orbit. We have already established that Luna still appears to move across the sky from East to West, but from an external perspective of the Terra/Luna system, Luna is moving retrograde.

Due to Terra’s spectacularly large tangential velocity about Sol, even when Luna is at eclipse position it is still moving significantly prograde relative to Sol.

Luna never moves retrograde from Sol’s perspective; it speeds up slightly when outside Terra and slows down slightly when inside Terra. {:tag=”aside” .block-info .iso7010 .m007}

To calculate Terran tangential velocity in rotation, we take its arc velocity and multiply it by the distance from the axis of rotation to the surface. At Driggs, Idaho, where I will be watching the eclipse, this is \(r_{T} \times \cos( 43° 43’ 24”)\).

Terra radius (in megameter): $$r_{T} := 6.371 Mm$$

[Tangential velocity of Driggs, ID][7]: $$v_{T} = \frac{\tau \times r_{T} \times \cos(43° 43’ 24”)}{p_{T}} = 336.12 \frac{m}{s}$$

Luna orbital radius: $$r_{L} := 384.4 Mm$$

[Luna tangential velocity][9]: $$v_{L} = \frac{\tau \times r_{V}}{p_{L}} = 1.022 \frac{km}{s}$$

Luna orbits in the same direction as Terra rotates, but with far more tangential velocity. This means that Luna is moving, relative to Terra, at 1.02km/s retrograde while people in Driggs, ID are moving retrograde at a mere 336 m/s, a quarter of the speed.

Terra orbits at 29.8 km/s. It’s important to keep in mind that there is no actual backward movement in our orbit, from Sol’s reference. Everything in this system is moving rapidly, rapidly prograde in Terra’s orbit.

Our observer in this case is orbiting on the Sol/Terra radius, keeping angular pace with Terra. From this rotating perspective, the Terran dayside and Luna will be moving in retrograde relative to the Terra/Luna barycenter.

Terran orbital prograde is to the West during the day, which means that during the day, the surface and Luna are both moving from West to East, Luna faster than the surface observers.

Thus, the Lunar shadow will cross Driggs, ID at a speed of \(v_{L} - v_{T} = 686 \frac{m}{s}\), moving from West to East.

During the eclipse, both Luna and Sol will be sliding across the sky from East to West, with Luna remaining relatively still in the sky while Sol moves behind it.

Why is the Eclipse Path Shaped Like That

This one’s simple to explain but hard to compute, so I’m not going to do the math.

In August, Terra’s rotation axis is pointed towards the sun, and on this particular Lunar orbit, Luna will be moving from North to South. This is why the path of eclipse is canted.

The reason the path is not a straight line is due to the way orbits work. The ground velocity of the shadow is coupled to the cosine of Lunar altitude in the sky. The linear velocity of Luna, projected to the tangent vector of Terra’s orbit, will not change largely, but will speed up (approaching zenith) and slow down (departing zenith) enough to be noticed on the ground track, and Terran rotation further adds to that, as the tangential velocity of the surface is coupled to the cosine of latitude.

I trust that paragraph explained why I didn’t do math for this section. I can do differential analysis on three independent arcs (Terran orbit, surface rotation, Lunar orbit) but I really, really don’t want to, especially when NASA already has, and has the result freely available for me to include at the top.

Also, keep in mind that Mercator maps at USA latitude have non-trivial distortion. The eclipse map would be simpler, in terms of the shadow path, if we used a Mercator projection aligned not to equator/North, but to the ecliptic and ecliptic-orthogonal. Then it’d be the straight(er) line of the Lunar orbit, distorted slightly due to the changing linear velocities of Luna and the surface relative to Terran core.

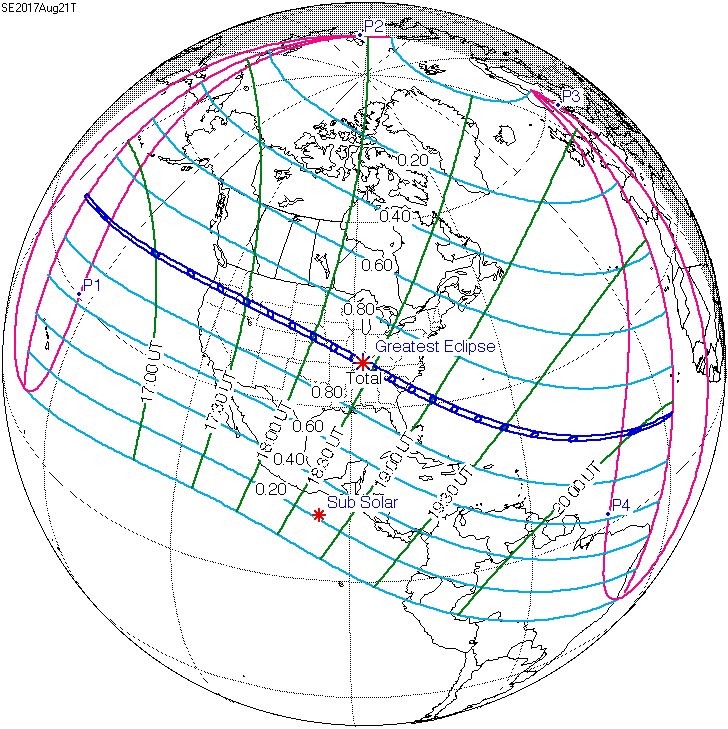

Wikipedia has a nice map which shows the projections onto Terran surface of solar geometry lines, which may be helpful in visualizing the overall layout.

A globe map of the eclipse-track over North America. Originally from Wikipedia. {:tag=”cite”} {:tag=”figcaption”} {:tag=”figure”}

Fin

These two are the only major things I’ve seen so far that I’m in a position to attempt to answer. If I come across anything else between now and 2017 Aug 21, I’ll update this.

Astrodynamics is complex.

[5]: http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=(2+*+pi+radian)+%2F+lunar+orbital+period

[9]: http://www.wolframalpha.com/input/?i=luna+orbital+circumference+%2F+luna+orbital+period