Battlestar Astrodynamica

Estimated reading time: .

I accidentally got way too invested in the astrodynamics of a complex stellar system and the mechanics of teleporting.

ContentsNote on how to read this article: everything with a green bar to the left of it can, and maybe should, be skipped. Also, if you turned off JavaScript, you’re going to have a bad time, because the math is rendered by you, not by me.

Background

I’m rewatching Battlestar Galactica (2003) and, having recently read an excellent hard sci-fi concerned with things like orbital dynamics, I realized I was also extremely concerned with the astrodynamics portrayed in the series. BSG is nominally a hard sci-fi story – it relies on very few “magic” elements, and sticks to firm rules about how things work in the story, based on real physics wherever possible but subject to story whimsy where not.

So I wanted to write down some quick sketches of astrodynamic realities of the show’s story, just for fun.

Articles of Faith

Let’s assume that, since the show takes place in our universe and in our past (Daybreak (Part 3)), that the rules of physics we currently know to be true are true. Specifically, linear momentum must be conserved. If we throw this out, this whole article evaporates, so, I’m going to keep it.

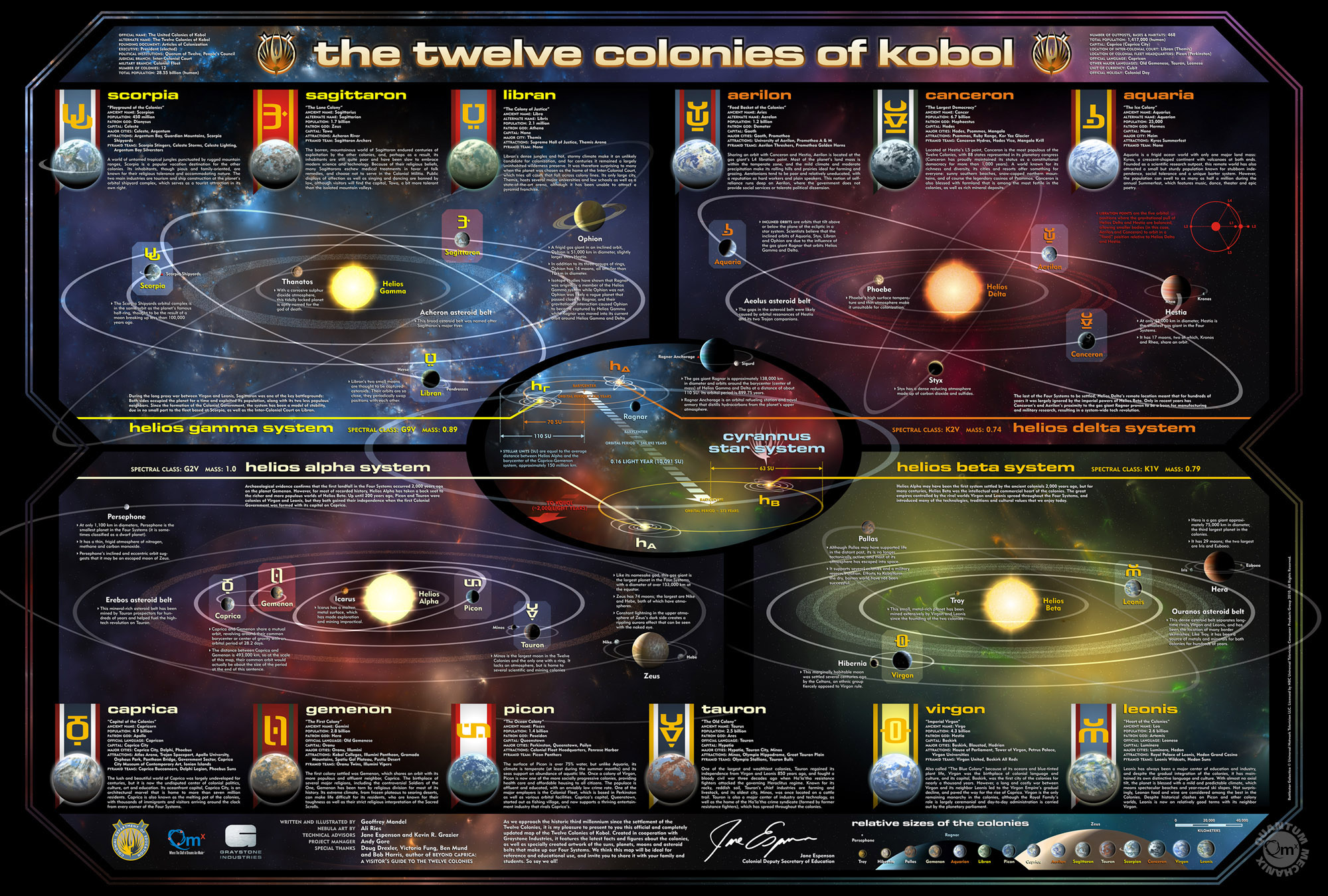

The map below was created by Kevin Grazier, the show’s science advisor, and Jane Espenson, a writer for Battlestar season 4 and the sequel show Caprica. The map was published in the IO9 article [“Detailed Map of Battlestar Galactica’s Twelve Colonies”][3].

Note that this picture has a lot of small text! If you can’t read it, don’t worry, I’ll write out all the important pieces as I go.

Orbital Motions

Alright, let’s put some numbers on paper.

To start: 1 SU is 150,000,000 km. This comes out to 1.003 AU, so you can treat them as the same. I’ll use the correct number for all my math; just think of an SU as the Earth-Sun distance. Let’s also assume that one Colonial year is equivalent to one Terrestrial year, since treating Caprica like Earth is just convenient.

The Cyrannus system consists of a barycenter (mutual center of gravitational attraction) between two binary-star systems. Each binary-star system has its own internal barycenter, and each star has planets.

For the rest of the article, I’ll use the word “Cyrannus” to refer specifically to the joint barycenter of the four stars.

Helios Α/Β and Γ/Δ Barycenters in Cyrannus

The Helios Α/Β and Γ/Δ barycenters orbit the Cyrannus barycenter at a diameter of 10,091 SU (radius 5,045) and period of 546,892 years. This gives us a linear speed of half a kilometer per second.

$$ \frac { 5,045 SU \times \frac { 150,000,000 km } { 1 SU } \times \tau } { 546,892 yr \times \frac { 31,557,600 sec } { 1 yr } } = 0.551 km/s $$

Helios Alpha in Helios Alpha/Beta

Helios Alpha orbits the Alpha/Beta barycenter at a radius of 63SU and period of 373 years (unclear, small text). The linear speed of that sun around its local barycenter is five kilometers per second.

$$ \frac { 63 SU \times \tau } { 373 yr } = 5.048 km/s $$

Caprica/Gemenon in Helios Alpha

Caprica is in a binary-planet system, so it orbits in a system probably like the Earth-Moon system. The barycenter of that system is 1 SU from Helios Alpha, with an orbital period of 1 year, so the Caprica-Gemenon barycenter has an orbital linear speed of 30 km/s about its star.

$$ \frac { \tau SU } { 1 yr } = 29.89 km/s $$

Caprica in Caprica/Gemenon

Their inter-planet radius is 246,500 km and their period is 28.2 days, so Caprica orbits the Gemenon barycenter at six hundred meters per second, slightly faster than the Α/Β system orbits Cyrannus’ total center.

$$ \frac { 246,500 km \times \tau } { 28.2 day } = 0.636 km/s $$

This means that, depending on where we are in the periods of each tier, an object in the Caprican orbital regime, such as, say, the Galactica in the miniseries, has speeds against the Cyrannus barycenter of up to 36 km/s.

The fastest an object can go in a tiered system like this is when all its orbits are moving in the same direction†, so when its motion around Gemenon lines up with: their motion around Helios Α, Α’s motion around Α/Β, and Α/Β’s motion around Cyrannus.

So that’s an example of the kind of layers of orbital motion that ships in the Battlestar Galactica universe need to handle when moving around. They only need to go as far up the stack as the lowest common reference frame of their destination, so travel between planets in the same system requires less work than travel between planets in different systems.

Linear Interstellar Travel

The Cyrannus system has four suns, and each pair has different binary-system characteristics against the total barycenter. The distances make inter-pair linear travel infeasible, so travel between pairs is only done by jumps, with no opportunity for matching destination velocity in transit.

There are 10,091 SU between the barycenters of the systems, and ≈65 SU of radius for each star, which means there are … 10,092 SU between the stars. Pythagoras is fun. Let’s solve a standard kinematic equation relating distance traveled to constant accelerating thrust. We’ll use the travel method from The Expanse: accelerate continuously to the halfway point, flip to point your engine at the destination, and decelerate to arrival.

The equation linking time under constant thrust to distance traveled is \(D = \frac{1}{2} \times A \times t^{2}\). We know the distance, not the time, so we want the inverse: \(t = \sqrt{\frac{2 \times D}{A}}\). We will solve for the time required to accelerate to the midpoint, 5,046 SU, and multiply that by two in order to decelerate back down to 0 over the same distance.

WolframAlpha says the total trip is nine and a half months.

This leads us directly to a very good question: after four and a quarter months of constant 1g thrust, … how fast are you going?

\(v = A \times t\) says that at the midpoint, ships are going 40% the speed of light. Since this is Battlestar Galactica, not [Revelation Space], I’m going to throw that answer away and try again, this time with a speed limit of 1% (still extremely fast).

Using \(t = \frac{v}{A}\), we can find that it takes three and a half days to reach 1%. Using \*D = \frac{1}{2} \times A \times t^{2}\), we can find that those three and a half days cover a measly 3 SU each. Since I chose a convenient speed limit of 1%, I don’t have to do any fancy kinematics. 0.16 light years, at 0.01 the speed of light, takes 16 years to transit. A week of burn time on the engines, and then a decade and a half on the float.

So rather than send colony ships back and forth forever, we have the jump drive.

Jump Drives

The FTL drive depicted in Battlestar Galactica is not a hyperfast accelerator like Star Wars uses, nor is it a subspace tunneler like Stargate.

This is the only† major piece of magic in the physics of the story, so we will assume that all our current understanding‡ of physics holds for the rest of the show. As I said at the outset, this means that linear momentum must be conserved. Now, two thousand words in, I’ll actually get to the point of that statement and all the orbital speed math I did.

Trampoline Mechanics

When ships jump from one point to another, they move instantaneously. From jump scenes in the miniseries, Razor, Exodus Part Two, and Someone To Watch Over Me, we can reasonably guess that the drives operate by bundling the spacetime occupied by the vehicle under transport and immediately sending it somewhere else.

Jump Calculation

The miniseries and 33 use a dolly-zoom effect, as well as actor behavior and dialogue, to indicate that a warping of spacetime occurs in the moments just before a jump.

Cally: “I hate this part.”

Dialogue in the miniseries (part one) indicates that the jump from Caprica space to Ragnar orbit is highly complicated and difficult, but still within the realm of possibility.

We are treated to the following conversation as prelude to the first jump of the show.

Cmdr. Adama: “Specialist. … Bring me our position.”

Col. Tigh: “You don’t want to do this.”

Adama: “I know I don’t.”

Tigh: “Because any sane man wouldn’t. It’s been, what, twenty, twenty-two years?”

Adama: “We trained for this.”

Tigh: “Training is one thing, but– if we’re off in our calculations by even a few degrees, we could end up in the middle of the sun.”

Adama: “No choice. Colonel Tigh, please plot a hyperlight jump from our position to the orbit of Ragnar.”

Tigh: “Lieutenant Gaeta, break out the FTL tables and warm up the computers. We are making a jump.”

While we are not treated to the dramatic and thrilling visuals of Lt. Gaeta cracking open a dusty tome and plugging navigation data into the computer, the allusion to transcendental-mathematics tables and astronomical computation conveys the idea of the manual and automated orbital mathematics of NASA missions, such as depicted in the excellent movie Hidden Figures.

Interestingly, fifty civilian ships make the same jump without any on-screen concern. Presumably, they have made long-distance jumps more routinely than a peacetime, forty-year-old, battlestar has.

The events of Scattered further support the assumption that FTL computation is hard, and requires significant work to account for stellar motion and vehicle velocities.

Moral of the story: jumps are commonplace enough that one-third to one-half of a random sample of ships have the drives to do them, but complex enough that a long-distance jump, especially across many orbital frames, requires significant effort. (I take exception to the comment “a small error could put us in the sun” since space is exceedingly empty, but hey, tension needs to be delivered somehow).

Jump Effects

There are four jump events in the series that stand out in their significant observed side effects.

In Exodus (Part 2), Galactica jumps directly into, and back out of, a planetary atmosphere. Its entry occurs at “99 thousand” (dialogue, units unsaid) and its exit occurs significantly closer to the ground. The arrival would presumably have displaced ambient air in a thunderclap, but 99 thousand is quite a lot of altitude whether in feet or meters. After a long fall to low altitude, Galactica jumps back to space, and this definitely results in a severe indraft and thunderclap.

In Razor, the Pegasus makes a jump from drydock, and the observing camera lingers after its departure. At the moment of jump, Pegasus is surrounded by venting atmosphere and flaming debris from the station’s wreckage, and after its jump, that gas is visibly, violently, indrafted into the Pegasus’ former volume.

Since this occurred in orbit and not in atmosphere, this behavior is not the result of fluid filling a new vacuum. We do not see the Pegasus’ arrival, so it is not known if the gas and fire was pulled into the jump, or into the vacuum left behind after the jump.

In Someone to Watch Over Me, a Raptor executes a jump while in close proximity to Galactica. In Daybreak (Part 2), many raptors jump from inside the Galactica’s starboard hangar wing. Both of these events result in shockwaves that travel through vacuum and damage the ship – the former results in several damaged sections and minor venting; the latter crumples the entire hangar wing.

Jumps are always illustrated by a bright spark that runs the keel of the jumping vessel before the jump, and then after the jump, a ring of light expands from where the center of the ship (presumably, the drive) used to be.

These effects are shown to be real, in-universe, effects and not just visual effects for us the viewers, because they cause visible shine and glare on characters observing the jump (Someone to Watch Over Me, Hot Dog observes Boomer depart). These expanding rings are likely the wavefronts of spacetime distortion in the jump vicinity.

Lastly, in The Oath we see that the Galactica’s structure near the jump drive has experienced severe metal fatigue and damage as a result of the countless jumps the ship has performed in its old age. In Daybreak (Part 3), Galactica’s final jump shatters the ship’s skeleton. The visual effects for the crippling of the ship are truly horrifying to watch, and I’m not going to try to describe them here.

Between the visual demonstrations in the first episodes and the physical effects in the last, we can conclude that spacetime does weird things before and after a jump in order to perform the swap. I’ll come back to this in the conclusion.

Consequences of Transit

Given that the jump process is solely a position swap, it therefore follows that linear momentum against the external reference frame is conserved. Ships that are under way before a jump are shown to remain under way after it (33).

Here’s where all the orbital mechanics work I did up above comes into play:

Ships have the same speed, presumably relative to the local galactic frame, on both sides of a jump. But the objects at the destination will almost certainly not have the same speed as the objects at the departure point.

A jump outward from a star, such as, say, from Earth orbit to Jupiter orbit, will result in the ship on arrival having Earth-orbit speeds but its new surroundings only having Jupiter-orbit speeds.

Earth orbit is 30 km/s against our star; Jovian orbit is 13 km/s. A teleport from Earth to Jupiter solar distance is an effective speedup of 17 km/s relative to local objects. This causes one immediate problem – 17 km/s is a lot of Δv; stationkeeping is impossible and a collision is both inevitable and catastrophic – and one slightly longer term problem: 30 km/s at Jovian distance will change the ship’s orbit from circular to extremely elliptic, with the ship immediately at periäpsis and accelerating outward.

A jump inward in the same system will have the opposite effect: from Jovian to Earth orbits will result in the vessel traveling 17 km/s too slowly, and the vessel will find itself at apoäpsis, falling inward. The inward fall is a less immediate problem than the fact that the ship will rapidly be overtaken by nearby objects with the same horrific consequences as the jump in the other direction.

This problem is only compounded by jumping across systems. The jump in the miniseries takes Galactica from Caprican space to Ragnar orbit. We already know that Caprican space requires roughly 36 km/s of speed against Cyrannus. I’m not going to do the math again, but from the map, we can solve that Ragnar space has a local speed of 3.65 km/s against the Γ/Δ barycenter, so, 4 km/s against Cyrannus. 32 km/s of Δv needs to be dumped somewhere either before or after the Galactica jumps.

We can presume that this is also why the ships are depicted as constantly under thrust – they’re always gaining or losing local linear speed to compensate for the last jump or prepare for the next.

Enter the Cylon

What does Galactica have that a Cylon basestar does not have? Besides a hearty stock of genetic diversity, of course.

Direct thrust engines

Galactica and all the human ships have big blue glowing engine nacells at their stern (yes, in a good universe they would be at the base).

Basestars have no direct thrust. Their raiders do, but the basestars themselves are never shown to do anything except pivot their arms and jump.

They’re still subject to the same rules about linear momentum as everything else is, so we have to conclude that either (a) they have reactionless drives, such as local gravity manipulation (boring, not supported by the show), or (b) (an option that is extremely supported by the show) their drives and pilots are incredibly good, and the pilots jump into and out of slingshot orbits around sufficient gravity wells to dump or collect Δv.

Cylon vessels are directly shown to have significantly better FTL than the human vessels are. They can jump raiders; equivalent human Vipers cannot jump. The Cylon superiority in FTL is also a direct plot point of A Disquiet Follows My Soul and its subsequent episodes.

They can jump far and precisely. They have organic/machine hybrid computers that are keenly aware of the universe and capable of rapid complex computation and analysis. Why would they use thrusters with the force necessary to accelerate a ship of that mass when they can jump across gravity wells and let astrodynamics do the work for them?

There’s No Such Thing As Free Speed

This article assumes conservation of momentum. Conservation of energy must also exist, and instantaneous travel up and down gravity wells grossly violates the conservation of gravipotential energy.

If the departure and destination localities are swapped, then the gravipotential energy of the whole system remains unchanged. This likely accounts for the shock and indraft effects we observe even in vacuum as high- and low- gravipotential energy regions equalize.

We don’t have direct proof that the two locations swap, because we are never shown both ends of a jump, both before and after it. In Lay Down Your Burdens (Part 1), the dreaded “we could jump into a [local navigational hazard]!” finally occurs, when a Raptor emerges from its jump inside a mountain rather than in the atmosphere. Since there is no geologic consequence from injecting “fifty tons of Raptor” (Boomer, Miniseries, Part 1) into a point surrounded by stone, we can presume it’s because the equivalent volume of rock was scooped out and dropped in interstellar space as a new asteroid.

I am not a physicist and I am drawing entirely on freshman year kinematics and theory for this whole article. But this isn’t a paper on how to make a jump drive; it’s an article explaining why the fictional TV show Battlestar Galactica requires less of a suspension of disbelief than one might expect for a saga about God, recurring and parallel evolution, angels, and sexy computers.

Thanks for reading. Lieutenant Gaeta is an unsung hero of the fleet.

So say we all.

Bibliography

- Battlestar Galactica

- Miniseries

- “Part One”. Ronald D. Moore, Christopher Eric James; Michael Rymer. 2003 Dec 8.

- “Part Two”. Ronald D. Moore. Christopher Eric James; Michael Rymer. 2003 Dec 9.

- Season 1

- Episode 1: “33”. Ronald D. Moore; Michael Rymer. 2004 Oct 18.

- Episode 2: “Water”. Ronald D. Moore; Marita Grabiak. 2004 Oct 25.

- Season 2

- Episode 1: “Scattered”. David Weddle, Bradley Thompson; Michael Rymer. 2005 Jul 15.

- Episode 19: “Lay Down Your Burdens (Part 1)”. Ronald D. Moore; Michael Rymer. 2006 Mar 3.

- Season 3

- Episode 4: “Exodus (Part 2)”. Bradley Thompson, David Weddle; Félix Enríquez Alcalá. 2006 Oct 20.

- “Razor”. Michael Taylor; Félix Enríquez Alcalá. 2007 Nov 24.

- Season 4

- Episode 14: “A Disquiet Follows My Soul”. Ronald D. Moore; Ronald D. Moore. 2009 Jan 23.

- Episode 17: “Someone to Watch Over Me”. Bradley Thompson, David Weddle; Michael Nankin. 2009 Feb 27.

- Episode 20: “Daybreak (Part 3)”. Ronald D. Moore; Michael Rymer. 2009 Mar 20.

- Miniseries

- [“Detailed Map of Battlestar Galactica’s Twelve Colonies”][3]. Anders, Charlie Jane. 2011 Jan 24.

- “The Solar System and Beyond is Awash in Water”. Dyches, Preston; Chou, Felicia. NASA JPL. 2015 Apr 7.

- “Mission status: SICK”: I have no idea, I saw it on Twitter once and saved it.

[3]: https://gizmodo.com/detailed-map-of-battlestar-galacticas-twelve-colonies-5742034